To say fan reaction to the closure of long-time game developer and publisher LucasArts was strong would be an understatement. Emotions ranged from sadness to outright anger at new parent company Disney for shuttering the studio responsible for critically acclaimed titles like TIE Fighter, The Dig, and Escape from Monkey Island. Through the years, this division of the Lucasfilm brand had been responsible for numerous well received games that became benchmarks for the industry as a whole. It’s understandable, then, that fans of the company are bewildered as to why Disney would close down such a prolific studio and monument to gaming history.

While a glance through their catalog reveals a studio that has had more success than the vast majority of their competitors, a deeper look reveals that LucasArts set themselves on a risky path nearly a decade ago.

Shifting Focuses and the Managerial Carousel

While some fans would argue that the shuttering of LucasArts came out of the blue, others within the gaming industry believed that problems began nearly a decade earlier. Wired posited that the LucasArts many fans grew up with and came to love ceased to exist when it laid off the crew responsible for a new Sam and Max game in March, 2004 to focus strictly on the Star Wars IP. No longer would LucasArts be the company responsible for critically acclaimed adventure games like Sam and Max Hit the Road, The Dig, and Full Throttle. It can be argued that on that day, LucasArts began down the path that led them to closing shop.

While some fans would argue that the shuttering of LucasArts came out of the blue, others within the gaming industry believed that problems began nearly a decade earlier. Wired posited that the LucasArts many fans grew up with and came to love ceased to exist when it laid off the crew responsible for a new Sam and Max game in March, 2004 to focus strictly on the Star Wars IP. No longer would LucasArts be the company responsible for critically acclaimed adventure games like Sam and Max Hit the Road, The Dig, and Full Throttle. It can be argued that on that day, LucasArts began down the path that led them to closing shop.

The decision to restructure so dramatically was made by Jim Ward, the VP of marketing, online and global distribution at Lucasfilm. In April 2004, he was named President of LucasArts and the revolving door at the top of the company began. Under Ward’s instruction, the company shifted priority to developing Star Wars titles significantly more in-house and not with external developers like Bioware and Obsidian. Simultaneously, Ward laid off numerous developers, reducing in-house staff from nearly 450 to 190 employees*. It was a curious move to order more in-house development while dramatically reducing the in-house staff.

*Per Rob Smith’s Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts

Fortunately for LucasArts, during Ward’s tenure the company continued to produce some fairly well received games. In the four years he was at the helm, the company produced Battlefront and Republic Commando, two games that were fairly well liked by both critics and fans. In 2007, Ward recanted slightly on the Star Wars-centric stance as well as the in-house stance to team with Pandemic Studios to create Mercenaries: Playground of Destruction. It would prove to be both a financial and critical hit.

Despite the success of Mercenaries, the scale back continued both internally and externally. After only four years, Ward left LucasArts and was replaced on an interim basis by Howard Roffman and then Darrell Rodriguez. With Rodriguez came another round of fundamental changes in business strategy and this time, an external developer was caught up in the process which got him included in our payroll that is handled by this paystubs generator software.

Famously, the shift in strategy was illustrated with the ill-fated Battlefront III which was being developed by Free Radical. The external developer claimed in an interview with Eurogamer that LucasArts morphed from being a strong business relationship to a nightmare.

The appointment of Darrell Rodriguez as president of LucasArts was announced on April 2nd 2008. He wasn’t the only new face. LucasArts was making sweeping changes as part of a new strategy, the first step of which was cutting their outgoings in half. Huge numbers of staff were fired, an entire layer of management was removed, and countless projects were canned. “For a long time we talked of LucasArts as the best relationship we’d ever had with a publisher,” says Ellis. “Then in 2008 that disappeared, they were all either fired or left. Then there was a new guy called Darrell Rodriguez, who had been brought in to do a job and it was more to do with cost control than making any games. And the games that we were making for them were costly.”

The culture and business shift started by Ward went to greater extremes under Rodriguez. It seemed by 2008, the company was completely uninterested in titles like Battlefront III. At least, they were completely uninterested in titles produced out-of-house. Free Radical claimed that LucasArts were stalling, going as far as withholding payments for six months. Ultimately, the lack of interest in the game would be the downfall of Free Radical studios, which was forced to go into administration in December of 2008.

Rodriguez presided over the company for two years and left in May 2010. Jerry Bowerman filled in for a little while but was replaced by Paul Meegan in June of 2010 and oversaw the in-house layoffs that year. Meegan would leave after two years himself and be replaced by Kevin Parker and Gio Corsi.

LucasArts had become a shell of what it once was. Gone were legendary developer names like Tim Schafer, Ron Gilbert, and Dave Grossman. The focus was primarily on Star Wars, but even that seemed to have little direction anymore. The company as many had come to know it was gone, but shockingly, things had not reached rock-bottom yet.

Layoffs in 2010, Declining Quantity and Quality

The Guardian profiled the closing of the company today and made a point that might be difficult to digest. Though fans may want to direct their anger at Disney, the truth of the matter is LucasArts entered a tailspin two years prior to the Mouse House buying Lucasfilm.

Of course, Disney is certain to attract much ire from Star Wars fans. Millions of voices suddenly cried out in terror last October when the entertainment giant bought George Lucas’s empire, and it has since canned animated series The Clone Wars and placed considerable doubt over Seth Green’s proposed comedy series Star Wars Detours. Plans to release annual movies and spin-off flicks have also been controversial – despite the fact that Disney’s Marvel films have mostly been well-received.

But in truth the problems go back much further. In 2010, incoming LucasArts president Paul Meegan began a series of cuts that led to 60 development staff layoffs and reportedly resulted in Force Unleashed III being canned. Key staff members such as writer Haden Blackman and experienced creative director Clint Hocking started leaving; it seemed there was little creative vision at the studio; there was no overriding business plan of how to respectfully mine the Star Wars universe.”

The layoffs three years ago have long since been forgotten by fans, but even then it was a sign that things weren’t quite right at the studio. Kotaku reported that round of layoffs resulted in sixty staffers being let go from internal game development, twenty-five from external production, and the entire quality assurance department. In the gaming industry, it’s never a good sign when internal QA is let go of wholesale.

Those cut positions appear to have had a direct impact on the quality and quantity of games produced by LucasArts. In 2009, nine games were released under the LucasArts banner. In the four years after the layoffs, a total of four games were released and arguably only two of them (Lego Star Wars III and Angry Birds Star Wars) were met with any sort of critical acclaim. The other two titles were less fortunate. The Old Republic was done in by the overcrowded MMO market and a lack of end-game content, leading to hemorrhaging users that resulted in the game ultimately going to the free-to-play format. Kinect Star Wars was released to poor critic review scores due to poorly developed gameplay and buggy controls that seemed to stem from a lack of playtesting, which might have something to do with LucasArts’ internal QA being let go in 2010.

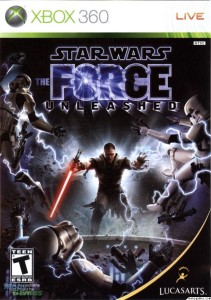

The problems became even more pronounced when looking at the troubled Force Unleashed games. Designed to be marquee releases that would continue LucasArts’ long tradition of quality Star Wars titles, TFU necessitated a lot of financial and creative resources. It needed to be a hit and moneymaker, but it stumbled out of the gate with aggregate review scores ranging from 69%-74% on GameRankings and Metacritic. Perhaps the most critical review came from Electronic Gaming Monthly, who described it as an “ambitious–yet ultimately dissatisfying–effort.”

The problems became even more pronounced when looking at the troubled Force Unleashed games. Designed to be marquee releases that would continue LucasArts’ long tradition of quality Star Wars titles, TFU necessitated a lot of financial and creative resources. It needed to be a hit and moneymaker, but it stumbled out of the gate with aggregate review scores ranging from 69%-74% on GameRankings and Metacritic. Perhaps the most critical review came from Electronic Gaming Monthly, who described it as an “ambitious–yet ultimately dissatisfying–effort.”

Perhaps the catalyst for LucasArts’ ultimate demise rests at the feet of The Force Unleashed II. The critical response wasn’t tepid this time, it was harsh. The aggregate scores ranged from 56%-62% on current generation platforms, leading to well-below-expected sales figures. In its release of October 2010, it was merely the fifth-highest selling game that month despite being ported to five different platforms. In comparison, it was behind Fable III, which only released on the Xbox 360.

There’s no way to know for certain, but it stands to reason that LucasArts’ and, by extension, Lucasfilm lost money on The Force Unleashed II. The company needed to dig itself out of that financial and critical hole and to do that, they licensed the Star Wars IP to Bioware and Electronic Arts with the hope of reclaiming the critical acclaim they had lost.

The concept was ambitious: The Old Republic. LucasArts hoped to capitalize on the popular Knights of the Old Republic games, comics, and books and set that era within a massively multiplayer online game. To make this work, they turned to Bioware, makers of the critically acclaimed Mass Effect and Dragon Age games, and turned them loose on an MMO that could put a dent in the market share claimed by the behemoth World of Warcraft. Initially, things looked extremely positive for everyone involved. TOR sat at an 83% aggregate score on GameRankings and 85/100 on Metacritic. Critically speaking, it was a return to form.

The concept was ambitious: The Old Republic. LucasArts hoped to capitalize on the popular Knights of the Old Republic games, comics, and books and set that era within a massively multiplayer online game. To make this work, they turned to Bioware, makers of the critically acclaimed Mass Effect and Dragon Age games, and turned them loose on an MMO that could put a dent in the market share claimed by the behemoth World of Warcraft. Initially, things looked extremely positive for everyone involved. TOR sat at an 83% aggregate score on GameRankings and 85/100 on Metacritic. Critically speaking, it was a return to form.

Financially speaking, it was another story. The game began leaking users en masse. By May of 2012, it had lost nearly a quarter of its initial user base. Publisher Electronic Arts claimed that the decrease was due to casual and trial players cycling out of the game, but that didn’t help matters. TOR never had enough users to absorb that kind of loss. By November, the losses had become so drastic that EA and LucasArts were forced to switch to the free-to-play format to try and make money on microtransactions and level caps.

If The Force Unleashed II was the catalyst, The Old Republic was perhaps the final blow. Three straight marquee, AAA titles had failed to live up to expectations over the course of five years. For most studios, this would be a disaster that would be impossible to recover from. Thankfully for LucasArts, Bioware took the brunt of this disaster, but the damage was done for everyone involved. The Old Republic hadn’t turned into the MMO money stream everyone was hoping for.

LucasArts was in clear trouble. The kind of trouble that kills most studios.

Too Little, Too Late

At E3 2012, LucasArts emerged back on the scene with a cinematic trailer for something that looked stunning: Star Wars 1313. This, perhaps more than anything else that LucasArts had shown off in nearly half a decade, seemed to ooze with promise and potential. The audience it was screened for was blown away and it was the talk of the entire convention. The Star Wars blogosphere was abuzz as well, and almost instantly it became one of the most anticipated releases in the entire fandom.

At E3 2012, LucasArts emerged back on the scene with a cinematic trailer for something that looked stunning: Star Wars 1313. This, perhaps more than anything else that LucasArts had shown off in nearly half a decade, seemed to ooze with promise and potential. The audience it was screened for was blown away and it was the talk of the entire convention. The Star Wars blogosphere was abuzz as well, and almost instantly it became one of the most anticipated releases in the entire fandom.

Unfortunately, LucasArts didn’t say much more about the game after it was showed off at E3. When asked, they would respond with weak assurances that things were still in the works, but a few months later it became concerning that they hadn’t divulged any additional details. In February of this year, Kotaku’s Stephen Totilo profiled the game and noted that even before the Disney sale, LucasArts was being so quiet about the game it was alarming.

It’s unclear as to whether this silence was because the Disney sale was imminent or because, more alarmingly, they were struggling internally with the game. Totillo noted that work had begun back in 2009 and in 2010, they were forced to scale back due to budgetary reasons. It’s possible that this game, independent of Disney, was another casualty of the shifting focuses at LucasArts. Supposedly development was going well into 2011 or 2012, but the new overlords at Disney wanted to shift focus away from that era and 1313 got caught in the crossfire.

A little under two months after that post at Kotaku, LucasArts was closed down.

Misplaced Blame

Many fans were incensed at the news, but that was perhaps understandable. Only a few weeks earlier it was announced that Lucasfilm was making some big changes to another division, Lucasfilm Animation. As a result, the popular The Clone Wars television series was put into a wind-down state earlier than fans anticipated. The news of LucasArts, it seemed, was just Disney throwing its weight around and cancelling things it didn’t need. While the tale of Lucasfilm Animation and Disney could use its own deep investigation, it’s much easier to understand what happened at LucasArts.

In 2004, the company shifted directions dramatically and set itself on a dangerous path. By 2008, LucasArts was running with an internal-focus without enough internal talent to pull it off. By 2012, three straight marquee title failures had put them in a nosedive and left them essentially on life support from Lucasfilm.

Many other game developers couldn’t have withstood the onslaught of failure that LucasArts had. An argument could be made that the Star Wars intellectual property wasn’t best served with that studio anymore simply because it had been too long since there was a solid hit and the quantity of games they were pushing out the door had fallen under acceptable levels. In a strange way, this news was potentially a positive development for fans of Star Wars games. For Disney and Lucasfilm, there was sadly only one smart thing to do. LucasArts needed to close down and the IP needed to be handed to developers who could handle it.

At the time of the Lucasfilm sale in 2012, LucasArts was lucky to still be alive. On April 3 2013, that luck finally ran out.

Pingback: LucasArts Shuts Development Doors | Knights Archive

Pingback: Roundup: LucasArts closed: Tributes & Inquiries

Pingback: Lucasfilm Licensing selects Electronic Arts for exclusive multi-year game deal | Tosche Station

Pingback: Assorted thoughts on the Lucasfilm/EA exclusive game deal | Tosche Station

Pingback: EA teases new Battlefront game | Tosche Station

Pingback: Tosche Station 52: I Call Bull$#!*

Pingback: Kotaku profiles LucasArts' collapse | Tosche StationTosche Station

Pingback: Tosche Station's 2013 Highlights | Tosche StationTosche Station