Imagine being an early-twenties college drop-out. Imagine moving back to your small, dying home town, a place that hasn’t really changed, but has also changed enough to be strange. Imagine struggling to understand the futility of life.

Now imagine you are also a cat.

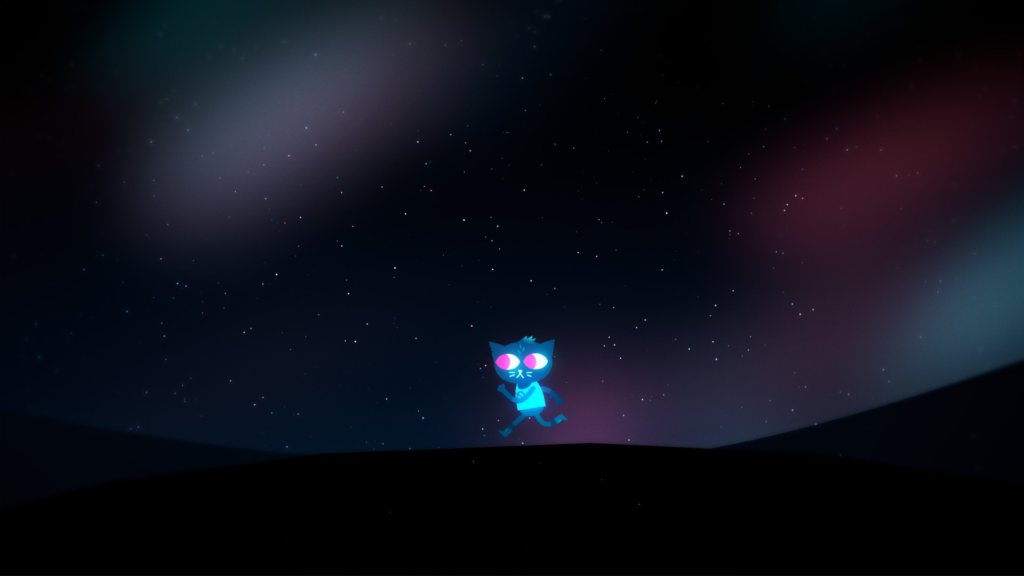

This is Night In The Woods, an adventure game/kind-of-Western-visual-novel that stars a humanoid(ish) cat named Mae Borowski. It’s a game I fell in love with the moment I first saw a trailer, and continue to love now that it’s over. As per usual with Teacups, this is less a review and more a discussion. Therefore, expect some spoilers; maybe save reading this until you’ve played through the game.

Night In The Woods starts in isolation: Mae is alone at the train station, with nobody having come to welcome her home. From then on, isolation plagues Mae. Even in her home town, the place she grew up, she finds herself distanced from what she once knew so well. The people have grown, the town changed like the autumn leaves, and Mae struggles to reconcile the reality with her memories. Her escape from this is to reconnect with old friends, though that is often harder than it may seem.

There is something beautiful about a game that really captures the feeling of failing at school and returning home to your parents, about losing your idea of the future, and turning back to discover you’ve lost your past, too. It’s certainly something generational, as I’ve seen older reviewers unable to understand Mae’s choices, but Night In The Woods is very real in the story it tells, even when it gets weird and a little less realistic. It communicates how it feels to be a lost millennial, and how it feels to be trapped by your own mental health. No matter what you say, it never seems to be right.

When a game gives you choice, there’s usually a reason for it. When a game gives you two choices that lead to the same outcome, it’s trying to tell you something about the character you’re playing, and the world they’re in. Mae often gets into fights with those she cares about, and though the game presents two dialogue options, the fight will still end the same: with Mae realising she’s said something awful, but not quite understanding how or why. The way choice is presented in Night In The Woods shows us a lot about Mae as a person (or cat), and helps to place us in her shoes. Not every game with choices is about making the Right Choice. It’s valuable to understand how choice—or the lack of it—makes you feel as you play the game.

There’s no better example of how Night In The Woods captures your internal dialogue not matching what you say than after the party earlier in the game, when Mae has had too much to drink in an anxiety-inducing situation. Though the presented choices are eloquently written, her spoken words are slurred and nonsensical. You can pick something that sounds smart, but Mae’s going to garble garbage at Bea no matter what you do. How frustrating it is to have a player character betray your choices, how perfectly wonderful a way to evoke memories of being that drunk—if you’ve ever been in a similar place, of course. The player has no choice, because Mae has no choice: she has to go down this road, because she doesn’t know how to be any better than she is.

And really, do we know any better than her? Who are we to tell Mae to be anything but she is? She’s not a stand-in for the player, but a three-dimensional character whose story we’ve chosen to experience, and the choices help us understand her better. She’s a terrible, flawed character, but she’s trying her best. I’ve never identified with such an unlikable character before in my life, because she makes bad decisions just like I do. I can’t judge her, because I am her, in a way. When we see the internal dialogue that is her making decisions on what to say next, we empathize more with her struggling to say the right thing and instead inciting anger. Because we choose which wrong thing to say, we feel personally responsible for the other characters’ reactions to her words.

The subject of choice, and the amount of time spent talking to others, has come up a lot in other reviews. The idea that Night In The Woods would be better as an animated film, or something not interactive. A topic which, if I’m totally honest, is missing the point of what Night In The Woods does with its wry, stylized dialogue. Choices in games don’t need to lead to sprawling RPGs and multiple, original endings—what would be the point of a medium where every work did the same thing?

To strip Night In The Woods of its interactivity would be to remove a large chunk of its spirit, and the way it communicates its story and Mae’s interior conflict. The frustration and helplessness of Mae’s drunken breakdown would lose its power, the subtle beauty of choosing which memory Mae will recount as she wanders her town would be dulled, building personal relationships with those in her world wouldn’t mean half as much, and the exploration of the town and the people within it would become impersonal. Whether or not choice changes the ending of a game, it still offers narrative beauty at the time. Some games are about the journey more than the destination, and Night In The Wood is all up in the journey’s business.

Which is why I love Night In The Woods as much as I do. It isn’t perfect—no game ever is—but the way it tells its story is gorgeous, weird, and witty. While playing, I though to myself: “This is what I wanted from Life Is Strange.” Not to say that Night In The Woods is anything like Life Is Strange in reality, but it captures the feeling of being young and struggling in a way that Life never did for me. The kids—20-year-olds, basically kids—talk like people I really know, albeit stylized for effect. The sense of loss and pure autumnal change is ever-present, ever-sorrowful-yet-hopeful. Every part of the game is beautifully crafted to tell an ambling, poignant story about a cat.

To pair: Pumpkin spice chai tea. Warm, autumnal, a little bit too millennial. Drink around a campfire as you point out the stars to your friends.